Insert Headline

Insert text here.

Insert Headline

Insert text here.

The Battle of Bunker Hill

by David J Samuels | June 17, 2025

The Battle of Bunker Hill, fought 250 years ago on June 17, 1775, near Boston, Massachusetts, was a pivotal engagement in the early stages of the American Revolutionary War. Colonial forces, under Colonel William Prescott, fortified Breed's Hill overlooking Boston Harbor. Though fought on Breed’s Hill, the battle exists in the nation’s memory as “The Battle of Bunker Hill” both because it was originally intended to be fought on Bunker Hill and because a British officer mismatched the two hills when drawing up a map of the area.

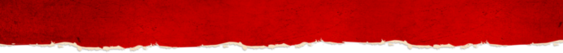

One officer, Colonel John Stark of New Hampshire (later Major General John Stark of the Continental Army) ordered the soldiers blocking the path of his regiment to stand aside if they wouldn’t help. Stark was able to march his men to support Colonel Prescott.

Despite Stark’s help, the American militia was outgunned and outmanned. With their ammunition depleted and their defenses faltering, the Americans eventually withdrew from the battlefield, allowing the British to claim victory.

African and Indigenous Americans at the Battle of Bunker Hill

The roots of the Battle of Bunker Hill lie in the tensions between the American colonies and the British Crown. Frustrated by perceived injustices and taxation without representation, colonial resentment grew, culminating in acts of defiance such as the Stamp Act Riots, Non-Importation Agreements, the violence that led to the Boston Massacre, and finally the Boston Tea Party. The British response, including the deployment of troops to quell dissent, only fueled the flames of rebellion.

By the spring of 1775, hostilities erupted into armed conflict with the battles of Lexington and Concord. Following those battles, the British Army and Royal Navy controlled the town of Boston and its harbor, but the surrounding areas were controlled by the fledgling American forces. The stage was set for a showdown.

The Path to War

The Strategic Importance

As dawn broke on June 17, British troops under the command of General William Howe launched a frontal assault on the entrenched colonial positions. Despite being outnumbered and outgunned, the American militia fiercely defended their makeshift fortifications, repelling multiple British advances with volleys of musket fire.

While technically a British victory, the Battle of Bunker Hill came at a heavy cost. British casualties numbered 1054, including 89 officers, while American casualties numbered 450 killed, wounded, or captured. The battle demonstrated the determination and courage of the colonial forces and served as a rallying cry for the American cause, garnering support for the Continental Army and the cause of independence from Great Britain.

Those on both sides of the conflict who had hoped for a peaceful reconciliation between the Crown and its American Colonies had hoped in vain. After the Battle of Bunker Hill, there was no turning back.

Paul Revere’s cousin, Benjamin Hichborn, wrote to John Adams about Doctor Warren, saying that a Royal Navy Lieutenant, a day or two after the battle, had gone back to Breed’s Hill, dug up Doctor Warren’s body and then:

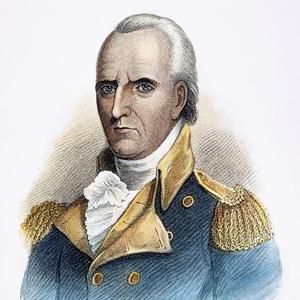

In the 19th Century, the Bunker Hill Monument was erected on the site of the battle. Even though the battle is named after the wrong hill the monument is on the correct hill. This means the Bunker Hill Monument is actually on Breed’s Hill! Today, the monument and the battle site are part of Boston National Historical Park and can be visited by tourists from around the world, around the country, and right here at home.

The Legacy of the Battle of Bunker Hill

Doctor Joseph Warren

The Bunker Hill Monument

Bunker Hill, along with nearby Breed's Hill, represented strategic positions overlooking Boston, which was occupied by the British Army and Royal Navy at that time. Understanding that they had to deny the high ground to the enemy, American forces under the command of Colonel William Prescott seized Breed's Hill on the night of June 16, 1775, despite orders to fortify Bunker Hill.

The Battle

(Note: These topics are worthy of further discussion and we hope to explore both in future posts.)

Many free and enslaved Africans fought in the Battles of Lexington and Concord and in the Battle of Bunker Hill and the rest of the American Revolution on the side of the colonists. This included both free and enslaved Africans, many of whom hoped to earn freedom and equality by showing their support for the American cause. Throughout the 19th Century, the service of African Americans in the American Revolution and later the War of 1812 would be used by 19th Century American abolitionists, Black and White, as evidence that African Americans had been instrumental in the founding of our nation and were deserving of American citizenship and equal rights. Even after the American Civil War of the 19th Century and the Civil Rights Movement of the 20th Century, this is still very much a work in progress.

Among the free and enslaved Africans who fought in the Battle of Bunker Hill were:

Barzillai Lew, Salem Poor, Titus Coburn, Alexander Ames, Cato Howe, Seymour Burr, Phillip Abbot, Isaiah Bayoman, Cuff Blanchard, Titus Coburn, Grant Cooper, Caesar Dickenson, Charlestown Eaads, Alexander Eames, Asaba Grosvenor, Blaney Grusha, Jude Hall, Cuff Haynes, Cato Howe, Caesar Jahar, Pompy of Braintree, Salem Poor, Caesar Post, Job Potama, Robin of Sandowne, New Hampshire, Peter Salem, Seasor of York County, Sampson Talbot, Cato Tufts, and Cuff Whitemore.

At least fifteen people indigenous to the North American continent (specifically the area the English called “New England”) fought in the Battle of Bunker Hill. This included members of the Mashpee Wampanoag, Hassanamisco Nipmuc, Tunxis, Mohegan, and Pequot tribes.

Among these were:

Joseph Paugenit of the Mashpee Wampanoag

Ebenezer Ephraim of the Hassanamisco Nipmuc

John Wampee of the Tunxis

Jonathan Occum of the Mohegan

Samuel Ashbow, Jr. of the Mohegan

John Ashbow of the Mohegan

The fifteen Indigenous Americans who fought at the Battle of Bunker Hill were just a fraction of those who fought in war. It is argued that the indigenous people of the thirteen colonies who fought in the American Revolutionary War on the side of our then fledgling nation, did so because they thought it would improve their situation and relationship with the colonists. To quote a Mashpee Wampanoag:

However, as the battle raged on, the colonial forces fighting on Breed’s Hill began to run low on ammunition and most of the rest of the American forces refused to join the fighting, fearing to run into artillery fire from the British Army and Royal Navy, despite desperate urging from their officers.

“These fellows say we won’t fight! By Heaven, I hope I shall die up to my knees in blood!”

"Spit in his face, jumped on his stomach, and at last cut off his head..."

“Stuffed the scoundrel with another Rebel into one hole, and there he and his seditious principles may remain.”

Doctor Joseph Warren was a Boston physician and a friend to men such as Samuel Adams, Paul Revere, and others. He was an ardent patriot and a leader in the movement. He eventually became President of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress. Shortly before the Battle of Bunker Hill, Doctor Warren was appointed Major General in the Massachusetts Militia.

Both Colonel Prescott and General Israel Putnam unsuccessfully tried to convince Doctor Warren to take command at the Battle of Bunker Hill. Aware that he had no military experience and would only hamper the effectiveness of the militia if he exercised his rank, Doctor Warren went to Breed’s Hill and fought alongside the militia as a private.

Early in the battle, Doctor Warren was heard to say:

Doctor Warren was killed when British forces charged the hill for the third time. After capturing Breed’s Hill, British soldiers stripped Doctor Warren naked, repeatedly bayoneted his corpse, and buried him in a shallow ditch.

A British Army Captain later wrote that he had:

Ten months after the Battle of Bunker Hill, Doctor Warren’s brothers and his good friend Paul Revere went to Breed’s Hill and retrieved the doctor’s remains. Doctor Warren had been badly mutilated during the battle, making it difficult to identify his body. Fortunately, Paul Revere had made false teeth for the doctor and was able to identify his remains when he recognized his own handiwork.

Doctor Warren’s remains were first buried in the Granary Burial Ground, then moved to St. Paul’s Church in 1825. In 1855, Doctor Warren’s remains found their final resting place in his family’s vault at Forest Hills Cemetery.

“We supposed a just estimate of the rights of man would teach them the value of the privileges of which [we] were deprived, and that their own sufferings would naturally lead them to respect and relieve ours.”

This did not come to pass. Regardless of their sacrifices, the indigenous peoples of the eastern seaboard of North America were no better off after the war than they were before it.

For example: at the beginning of the war, the Massachusetts Provincial Congress promised the Passamaquoddy, Malicite, and Penobscot that large tracts of tribal land in Maine would be set aside for them in return for their service on the Northern border. After the war, the state of Massachusetts broke their word. They confiscated these supposedly protected tribal lands and sold them and used the proceeds to pay the back salaries of white Massachusetts soldiers.

The stories of these Black and Indigenous soldiers are not footnotes — they are central to the story of the Revolution. Their courage and sacrifice deserve remembrance not only in the context of their time, but as part of an ongoing conversation about justice, freedom, and who gets to be counted in the American narrative.

As we continue to examine this history, we do so not simply to honor the past, but to reckon with its legacy.