Insert Headline

Insert text here.

Insert Headline

Insert text here.

The Midnight Ride in Verse:

by David J Samuels | April 24, 2024

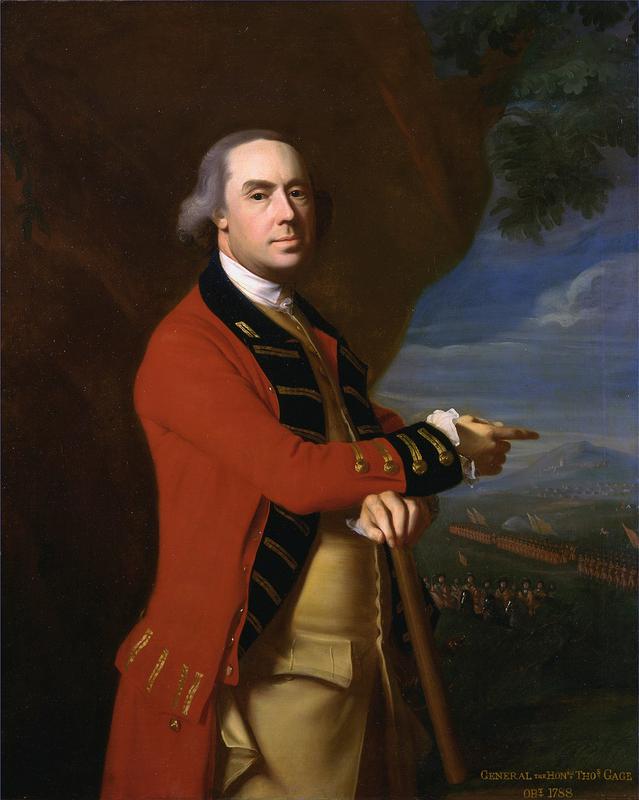

April 18th, 2025 is the 250th anniversary of the Midnight Ride of Paul Revere. Revere (pictured left) has been remembered in books both fiction and nonfiction, classrooms, walking tours, trolley tours, boat tours, and so on. He’s also been memorialized in verse, and he’s not the only person from that famous night to be remembered that way.

We all know the famous poem Paul Revere’s Ride, composed by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Many of you probably learned part of it in school as children. If you’ve ever participated in our Tour of the Freedom Trail program, then you know that the poem is not at all accurate. It was written in 1860 and first published in the January 1861 issue of Atlantic Monthly. The poem was a call to arms for the American Civil War.

Paul Revere

For a man only famous for one night of his life, there’s still a lot to say about Paul Revere. The best place to learn about Paul Revere is the Paul Revere House (pictured left) in Boston’s North End, which I encourage you to visit. Rather than paraphrase their work, I’m including a link to their biography of Paul Revere. If you visit Boston, be sure to stop in and see them. You won’t regret it.

If you’re lucky, you may be in town when Jude Kalaora of History-At-Play is performing her one woman show about Rachel Revere (Paul’s second wife). If you are, be sure to catch it if you can. Jude also portrays many other women of historical significance, including her most famous and most popular piece: A Revolution of Her Own, which is the story of Revolutionary War soldier Deborah Samson.

Paul Revere’s Ride

By Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

LISTEN, my children, and you shall hear

Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere,

On the eighteenth of April, in Seventy-five;

Hardly a man is now alive

Who remembers that famous day and year.

He said to his friend, “If the British march

By land or sea from the town to-night,

Hang a lantern aloft in the belfry arch

Of the North Church tower as a signal light, —

One, if by land, and two, if by sea;

And I on the opposite shore will be,

Ready to ride and spread the alarm

Through every Middlesex village and farm,

For the country folk to be up and to arm.”

Then he said, “Good night!” and with muffled oar

Silently rowed to the Charlestown shore,

Just as the moon rose over the bay,

Where swinging wide at her moorings lay

The Somerset, British man-of-war;

A phantom ship, with each mast and spar

Across the moon like a prison bar,

And a huge black hulk, that was magnified

By its own reflection in the tide.

Meanwhile, his friend, through alley and street,

Wanders and watches with eager ears,

Till in the silence around him he hears

The muster of men at the barrack door,

The sound of arms, and the tramp of feet,

And the measured tread of the grenadiers,

Marching down to their boats on the shore.

Then he climbed the tower of the Old North Church,

By the wooden stairs, with stealthy tread,

To the belfry-chamber overhead,

And startled the pigeons from their perch

On the sombre rafters, that round him made

Masses and moving shapes of shade, —

By the trembling ladder, steep and tall,

To the highest window in the wall,

Where he paused to listen and look down

A moment on the roofs of the town,

And the moonlight flowing over all.

Beneath, in the churchyard, lay the dead,

In their night-encampment on the hill,

Wrapped in silence so deep and still

That he could hear, like a sentinel’s tread,

The watchful night-wind, as it went

Creeping along from tent to tent,

And seeming to whisper, “All is well!”

A moment only he feels the spell

Of the place and the hour, and the secret dread

Of the lonely belfry and the dead;

For suddenly all his thoughts are bent

On a shadowy something far away,

Where the river widens to meet the bay, —

A line of black that bends and floats

On the rising tide, like a bridge of boats.

Meanwhile, impatient to mount and ride,

Booted and spurred, with a heavy stride

On the opposite shore walked Paul Revere.

Now he patted his horse’s side,

Now gazed at the landscape far and near,

Then, impetuous, stamped the earth,

And turned and tightened his saddle-girth;

But mostly he watched with eager search

The belfry-tower of the Old North Church,

As it rose above the graves on the hill,

Lonely and spectral and sombre and still.

And lo! as he looks, on the belfry’s height

A glimmer, and then a gleam of light!

He springs to the saddle, the bridle he turns,

But lingers and gazes, till full on his sight

A second lamp in the belfry burns!

A hurry of hoofs in a village street,

A shape in the moonlight, a bulk in the dark,

And beneath, from the pebbles, in passing, a spark

Struck out by a steed flying fearless and fleet:

That was all! And yet, through the gloom and the light,

The fate of a nation was riding that night;

And the spark struck out by that steed, in his flight,

Kindled the land into flame with its heat.

He has left the village and mounted the steep,

And beneath him, tranquil and broad and deep,

Is the Mystic, meeting the ocean tides;

And under the alders that skirt its edge,

Now soft on the sand, now loud on the ledge,

Is heard the tramp of his steed as he rides.

It was twelve by the village clock,

When he crossed the bridge into Medford town.

He heard the crowing of the cock,

And the barking of the farmer’s dog,

And felt the damp of the river fog,

That rises after the sun goes down.

It was one by the village clock,

When he galloped into Lexington.

He saw the gilded weathercock

Swim in the moonlight as he passed,

And the meeting-house windows, blank and bare,

Gaze at him with a spectral glare,

As if they already stood aghast

At the bloody work they would look upon.

It was two by the village clock,

When he came to the bridge in Concord town.

He heard the bleating of the flock,

And the twitter of birds among the trees,

And felt the breath of the morning breeze

Blowing over the meadows brown.

And one was safe and asleep in his bed

Who at the bridge would be first to fall,

Who that day would be lying dead,

Pierced by a British musket-ball.

You know the rest. In the books you have read,

How the British Regulars fired and fled, —

How the farmers gave them ball for ball,

From behind each fence and farm-yard wall,

Chasing the red-coats down the lane,

Then crossing the fields to emerge again

Under the trees at the turn of the road,

And only pausing to fire and load.

So through the night rode Paul Revere;

And so through the night went his cry of alarm

To every Middlesex village and farm, —

A cry of defiance and not of fear,

A voice in the darkness, a knock at the door,

And a word that shall echo forevermore!

For, borne on the night-wind of the Past,

Through all our history, to the last,

In the hour of darkness and peril and need,

The people will waken and listen to hear

The hurrying hoof-beats of that steed,

And the midnight message of Paul Revere.

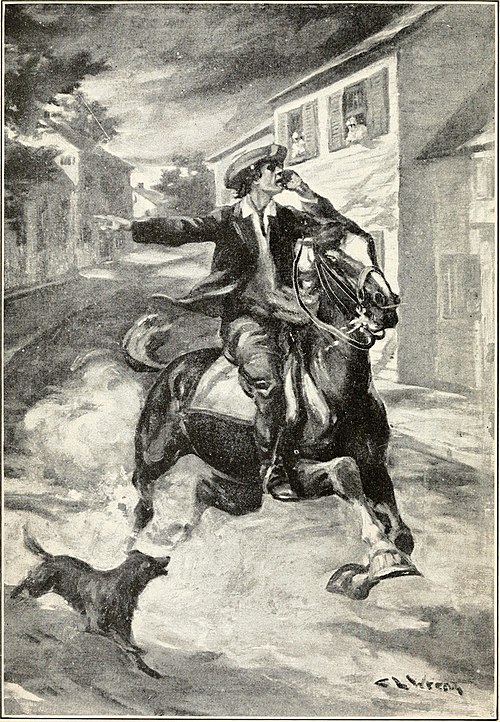

William Dawes (pictured left) was born in Boston, on April 6th, 1745. He trained as a tanner and was an active member of Boston’s Militia.

William Dawes & Samuel Prescott

Listen my friends and you shall hear

A bunch of garbage I pulled right out of my rear

I must admit I’m not an author or poet

And from what you’re going to read you too shall soon know it…

So sit back and enjoy this gobble-de-gook

Because I write this stuff, my friend writes the book

Twas early one morning on April Nineteenth 1875

When Samuel Prescott made his most famous ride

Who is Sam Prescott you may want to know

He rode with Revere but has no credit to show

He met up with Dawes and the famous Paul Revere

They rode all together to tell the colonists that danger was near

Our trio met up with four British spies

Who caught Paul Revere, but not this Prescott guy

On horseback in darkness our hero Sam ran

And pulled a 180 some dumb British man

And off through the forest he darted and ducked

To warn the townsfolk of Concord they were about to get invaded.

After warning Concord it was off to Acton, Mass.

To tell those who lived their to hurry their brass**

The British were coming and coming up fast

With their guns ready and loaded and ready to clash

Out of the bedroom and onto the floor

A fifty-yard dash to the bathroom door

So was the stunt that Sam’s Brother Abel

Had to run quickly in route to the stable

For Abel you see would take it from here

And Samuel went back to see the folks in Concord kick some rear

Yes Sam went back to see the Brits and colonists fight

Then tended to the wounded with all of his might *

History you see is an awful political game

Sam did the work and Revere got the fame

But now you all know what happened that night

Paul Revere got captured, but Sam Prescott got the colonists ready to fight

So now that you’ve listened to my rambling verses

When folks talk of the great Revere you now know what the truth is

Thanks to Sam Prescott, a true American Hero

And with the rhymes of this poem, he’s no longer a zero.

Israel Bissell… or was it Issac… or maybe both?

Inconsistencies in recording of this man or these men’s names, birthdates, birthplaces, and possible misinterpretations of events by historical societies have led to a great deal of confusion as to whether there was one rider named Israel Bissell or one rider named Issac Bissell or two riders, one name Israel Bissell and the other named Issac Bissell. Regardless, it is believed that Israel (or Issac, or both) rode farther and faster than Revere, Dawes, and Prescott, by a lot. The tale is incredibly convoluted, so we won’t go into it here.

Issac got zero love on the poetic front, but Israel was blessed with two poems.

The Midnight Ride of William Dawes

The Midnight Ride of William Dawes was composed by Helen F. Moore and published in an 1896 edition of Century Magazine.

I am a wandering, bitter shade,

Never of me was a hero made;

Poets have never sung my praise,

Nobody crowned my brow with bays;

And if you ask me the fatal cause,

I answer only, "My name was Dawes"

'Tis all very well for the children to hear

Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere;

But why should my name be quite forgot,

Who rode as boldly and well, God wot?

Why should I ask? The reason is clear --

My name was Dawes and his Revere.

When the lights from the old North Church flashed out,

Paul Revere was waiting about,

But I was already on my way.

The shadows of night fell cold and gray

As I rode, with never a break or a pause;

But what was the use, when my name was Dawes!

History rings with his silvery name;

Closed to me are the portals of fame.

Had he been Dawes and I Revere,

No one had heard of him, I fear.

No one has heard of me because

He was Revere and I was Dawes.

Samuel Prescott Poem

The Samuel Prescott poem was composed by Ben B of Springfield, Nebraska and published in 2009 on www.smartalecksguide.com where you can also find humorous writings and stories about American History and other topics. Ben got the year of the ride wrong. It should be 1775, not 1875, but that might be a typo on his part, I’m not sure.

Dawes was a trusted Son of Liberty. On the night of April 18th, 1775, when it became clear that the British Army planned to make its move, Doctor Joseph Warren (pictured left) told Dawes to ride out for Lexington to warn John Hancock and Samuel Adams, who had taken refuge there. While Revere was to be rowed across the Charles River to Charlestown where he would pick up a horse and ride to Lexington himself, Dawes sneaked out of Boston via the land route, just before the British Army locked down the town.

Dawes arrived in Lexington around midnight, about the same time as Paul Revere arrived. Technically, the two men were done for the night, having completed their mission by warning Samuel Adams and John Hancock of the approaching British troops. However, concerned that the troops might have the weapons and ammunition stored at Concord as their goal, Dawes and Revere set off together towards that town to warn them.

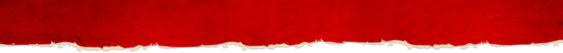

After the Boston Tea Party in December of 1773, Lieutenant General Thomas Gage (pictured right) of the British Army became the military governor of Massachusetts and occupied Boston to restore order. One of his plans involved confiscation of all of the cannon belonging to the Massachusetts Militia. William Dawes may have been involved in securing some of these cannon, protecting them from confiscation by the British Army.

Along the way to Concord, Dawes and Revere were joined by Doctor Samuel Prescott, a twenty-three year old physician from Concord. Prescott was traveling home after visiting a “lady friend” in Lexington. Upon hearing of their plans, Doctor Prescott decided to join them. Being from Concord, he felt the message would be taken more seriously by his neighbors if it came from him rather than from strangers.

The trio encountered a British scouting party. Dawes attempted a daring escape. He succeeded in escaping, but it was anything but daring. He ended up being thrown from his horse and walking back to Lexington.

Prescott actually made a daring escape and completed the ride to Concord, successfully warning the militia there.

Revere was captured by the British party, but ultimately released, albeit without his horse.

Israel Bissell’s Ride

By Gerard Chapman

Listen, my children, and you shall hear

Of Israel Bissell of yesteryear:

A poet-less patriot whose fame, I fear,

Was eclipsed by that of Paul Revere.

He lacks the renown that accrued to Revere

For no rhymester wrote ballad to blazon his fame;

But Bissell accomplished—and isn’t it queer?—

A feat that suggested Revere’s to be tame.

And yet is unknown to all but the few

Who, intrigued by the hist’ry of exceptional deeds,

Wish now to pay homage to Bissell long due

To him who filled one of the colonies’ needs.

’Twas the nineteenth of April in ’seventy-five,

The day that Paul’s ride was brought to a pause

(That war-warning which was made to survive

By Longfellow’s preference for him over Dawes),

That Bissell went south to carry the post

To patriot folk in Jersey and Penn.

And despite that his route was much longer than most

(It passed over hill, through valley and fen),

He carried the news of Britain’s attack

And the Middlesex farmers’ resolute stand,

And asked that the faraway colonists back

Their Boston compatriots’ stout-hearted band.

Down through Connecticut, down through New York,

He spread the alarm far and wide.

Across the wide Hudson he passed like a cork:

He rode through New Jersey, and on the far side

Attained Pennsylvania at last.

His trip cost two horses that under him died;

Never before had man gone so fast

The distance that Bissell made on his long ride.

He reduced the trip time from six to four days

To take to the men on the Delaware’s shore

The Patriots’ call for a blaze

Of resistance to Britain and war!

So men from New York, Philadelphia too,

Joined men from New Jersey in telling the King

That henceforth the Colonists wanted their due

In matters of government, and everything

That affected the lives of men who required

The unfettered right to control their own fate.

When such was denied them, these men were inspired

To proclaim to all mankind a newly-formed state.

We all know the fruit of the joining of forces:

How King George and Great Britain were defeated in war;

To Israel Bissell and his galloping horses

We now render tribute that was due him before.

I Bissell’s Ride

By Clay Perry

Listen, my children, to my epistle

Of the long, long ride of Israel Bissell,

Who outrode Paul by miles and time

But didn’t rate a poet’s rhyme.

A postman was this Israel Bissell.

Who on his horse, sped like a missile

On April nineteenth, seventy-five,

And few there are who are now alive

Who’ve read of that ride with the “Call to Arms”

Which summoned men with war’s alarms.

At Watertown where the Call was writ

And Bay State Congress then did sit.

He started out at ten o’clock

With words that all the world would rock;

He galloped on from town to town

His steed, exhausted, fell to the ground.

New Haven, first, where Arnold’s force

Of Yale militia took to horse,

And sped to Cambridge for the fight

Against the British, day and night.

Next to the farm where Putnam plowed

To whom he read the Call, aloud;

“To arms, to arms!” to all he cried

A second horse fell down and died.

And still he rode; another steed

Was saddled swiftly for his need.

Four days and nights he sped along,

And eight hours more, still going strong,

Until at Philly’s City Hall

He came and handed in the Call.

Now Continental Congress knew

The war was on, and those words flew

Afar and wide, the Colonies o’er

And warned the Redcoats from our shore,

The Call was relayed here and there.

Its winged words flew through the air

Were heard in Wall Street at New York,

And mustered many for the work.

When the war ended, Bissell came

To Berkshire where he made his claim

To land in Hinsdale, on a hill

And lived and labored there until

Death came, and on another hill

His grave is kept most tenderly

Because his ride helped make us free.

But on the simple marble stone

His name and dates are carved, alone;

No record of his daring ride,

But only that he lived and died

So here’s a tribute, poor and plain,

To him who dashed through April rain

And roused more Minute Men to arms

From town and city, shop and farm,

Than any other man alive.

In the year seventeen-seventy-five,

Two hundred twenty years ago

He outrode Paul and Will Dawes too.

One of the common misconceptions about the Midnight Ride of Paul Revere is that Revere was the only rider. There were many other riders that night, and I’ve found poems about three of them. None of the poets in question were as eloquent as Longfellow, but then again, that’s why he’s Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

Two of the other riders achieved some fame on Boston’s Freedom Trail: William Dawes and Doctor Samuel Prescott. One is not only less famous, but historians are not entirely sure if we got his name right. Some say his name was Israel Bissell, others say Isaac Bissell, and some say Israel and Isaac were in fact two different people! And, as I said, there were many others, but we’re just going to focus on the riders with poems I could find. I hope you enjoy this look at how people have remembered this famous event in verse over the years.